About Us | Father of Red Cross

Father of Red Cross

Father of Red Cross

Jean Henry Dunant

Born: 8 May 1828, Geneva, Switzerland

Died: 30 October 1910, (aged 82) Heiden, Switzerland

Citizenship: Swiss

Occupation: Social activist, businessman, writer

Religion: Calvinism (early years), non-religious in later life

Role: Originator Geneva Convention (Convention de Genève), Founder of the International Committee of the Red Cross, Geneva

Field: humanitarian work, peace movement

Awards: Nobel Peace Prize (1901)

Biography of Jean Henry Dunant

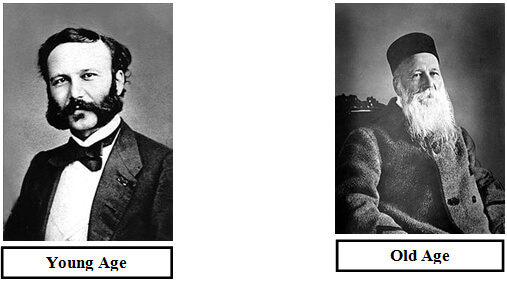

Life of Jean Henry Dunant has contrasts it famines study he was born into a wealthy home but died in a hospice, in middle age he juxtaposed great fame with total obscurity and success in business with bankruptcy; in old age he was virtually exiled from the Genevan Society of which he had once been an ornament and died in a lonely room, leaving a bitter testament. His passionate humanitarianism was the one constant in his life, and the Red Cross his living monument.

The Geneva household into which Henry Dunant was born was religious, humanitarian and civic-minded. In the first part of his life Dunant engaged quite seriously in religious activities and for the while in full time work as a representative of the young men’s Christian Association, traveling in France, Belgium and Holland.

At the age of 26 years old, Dunant began a position with one of Geneva’s largest banking houses in North Africa and Sicily. While knowing this position would produce his income, Dunant continued to work for charitable causes and established a YMCA outpost in Algeria. As a writer, he published his travel observations of North Africa. Having served his commercial apprenticeship. Dunant Devised a daring financial scheme, making himself president of the Financial and Industrial Company of Mons-Gemila Mills in Algeria to exploit a large tract of land.Needing water rights, her resolved to take his appeal directly to Napoleon III. Undeterred by the fact that Napoleon was in the field directing the French armies who, with the Italians, were striving to drive the Austrians out of Italy, Dunant made his way to Napoleon’s headquarters near the northern Italian town of Solferino. He arrived there in time to witness, and to participate in the aftermath of, one of the bloodiest battles of the nineteenth century. In 1859, a battle was raging at the town of Solferino in Northern Italy. His awareness and conscience (honed) sharpened, he published in 1862 a small book “A memory of Solferino” the book destined to make him famous.

A Memory has 3 themes. (1) The battle (2) depicts the battlefield after the fighting i.e. chaotic disorder, despair unspeakable and misery of every kind. And tells the main story of the effort to care for the wounded in the small town of Castiglione (3) A plan – The nations of the world should form relief societies to provide care for the wartime wounded; each society should be sponsored by a governing board composed of the nation’s leading figures, should appeal to everyone to volunteer, should train these volunteers to aid the wounded on the battlefield and to care for them later until they recovered.

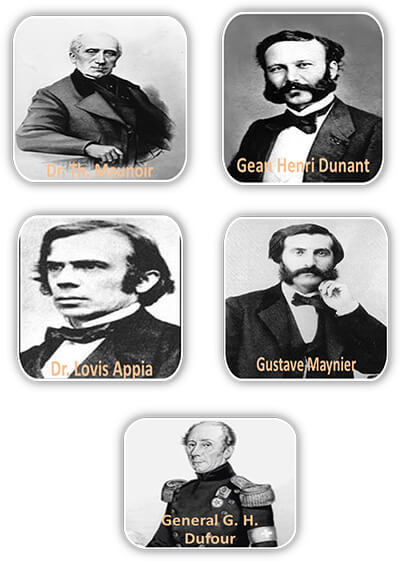

On February 7, 1863, the Geneva Society for Public Welfare appointed a committee of five, including Dunant, to examine the possibility of putting this plan into action. With its call for an international conference, this committee, in effect, founded the Red Cross. Dunant, pouring his money and time into the cause, traveled over most of Europe obtaining promises from governments to send representatives. The conference, held from 26 to 29, with 39 delegates from 16 nations attending, approved some sweeping far-reaching resolutions and laid the groundwork for a gathering of representatives. On August 22, 1864, 12 nations signed an international agreement, commonly known as the Geneva Convention, agreeing to guarantee neutrality to sanitary personnel, to expedite supplies for their use, and to adopt a special identifying logo – in virtually all instances a red cross on a white background.

Dunant had transformed a personal idea into an international agreement. But his work was not finished. He approved the efforts to extend the scope of the Red Cross to cover naval personnel in wartime, and in peacetime to alleviate the hardships caused by natural calamities. In 1866 he wrote a brochure called the Universal and International Society for the Revival of the Orient, setting forth a plan to create a natural colony in Palestine. In 1867 he produced a plan for a publishing venture called ‘International and Universal Library’ to be composed of the great master pieces of all time. In 1872 he convened a conference to establish the ‘World Alliance of order and civilization’ which was to consider the need for an international convention on the handling of prisoners of war and for the settling of international disputes by courts of arbitration father than by war.

The eight years from 1867 to 1875 proved to be a sharp contrast to those of 1859-1867. In 1867 Dunant was bankrupt. The water rights had not been concentrating his attention on humanitarian pursuits, not on business ventures, after the disaster, which involved many of his Geneva friends; Dunant was no longer welcome in Geneva Society. Within a few years he was literally living at the level of the beggar. There were times, he ate crust of bread, blackened his coat with ink, whitened his collar with chalk, slept out of doors.

For the next twenty years, from 1875 to 1895, Dunant disappeared into loneliness. After brief stays in various places, he settled down in Heiden. And there, in room 12, he spent the remaining eighteen years of his life. Not, however as an unknown. After 1895 when he was once more rediscovered, the world heaped prizes and awards upon him.

Despite the prizes and the honors, Dunant did not move form Room No. 12 upon his death, there was no funeral ceremony, no mourners, no cortege. Dunant was died on October 30, 1910. In accordance with his wishes he was carried to his grave like a dog.

Dunant had not spent any of the prize monies he had received. He bequeathed some legacies to those who had cared for him in the village hospital, endowed a free bed that was to be available to the sick among the poorest people in the village, and left the remainder to benevolent enterprises in Norway and Switzerland.

8 May 1828: Born

At the age of 26 years old(around 1854): Dunant began a position with one of Geneva’s largest banking houses in North Africa and Sicily.

1859: A battle was raging at the town of Solferino in Northern Italy

1862: He published a small book “A memory of Solferino”

1863: The result was the establishment of the International Committee of the Red Cross

February 7, 1863: The Geneva Society for Public Welfare appointed a committee of five. With its call for an international conference, this committee, in effect, founded the Red Cross. 16 nations has attended the conference.

August 22, 1864: 12 nations signed an international agreement, commonly known as the Geneva Convention

In 1866: He wrote a brochure called the Universal and International Society for the Revival of the Orient

1867: He produced a plan for a publishing venture called ‘International and Universal Library’

In 1872: He convened a conference to establish the ‘World Alliance of order and civilization’ which was to consider the need for an international convention on the handling of prisoners of war and for the settling of international disputes by courts of arbitration father than by war.

1867 to 1875 : 1867 to 1875 proved to be a sharp contrast to those of 1859-1867. In 1867 Dunant was bankrupt.

1859-1867:Good Time, good work

1867 to 1875: Bad Time begins

from 1875 to 1895: Dunant disappeared into loneliness

After 1895: When he was once more rediscovered, the world heaped prizes and awards upon him.

30 October 1910: Died (aged 82)